Just over two years ago, on May 25th, 2020, George Floyd was murdered by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. The shocking video of the incident quickly circulated across the internet through social media. Mr. Floyd’s murder sparked countless protests across the country and globe in the months that followed, capturing the public attention and initiating a national resurgence of the civil rights movement, often described as a “racial reckoning.”

Individuals, organizations, industries, and institutions across the country were again forced to acknowledge the realities of systemic racism in modern America. Journalism and news media were no exception. Media organizations in particular have a responsibility to model anti-racist practices not only in their internal policies and actions, but in their public-facing role of crafting narratives and framing national discussion as well. Researchers are finding impacts of this already – our own news analysis after the 2014 death of Michael Brown showed increased media coverage and discussion of the deaths of people of color at the hands of police. Another analysis of digital news following Mr. Floyd’s murder showed similar trends of increased coverage which mostly portrayed protestors positively. Mr. Floyd’s death and the ensuing Black Lives Matter protests dominated public discussion and demanded cultural changes - how has the media landscape shifted since then?

Acknowledging a Problematic History

Newsrooms have historically been, and continue to be, predominantly white. Majority white newsrooms were criticized following their coverage of the Civil Rights Movement in the Kerner Commission’s report of 1968, and in 1978, the American Society of News Editors (ASNE) made a commitment to greater newsroom diversity and declared a goal that newsrooms would be reflective of their community demographics by 2000. In 1998, only 11.5% of daily newspaper reporters were journalists of color, still far below the stated 26% goal. The ASNE then postponed its goal date to 2025, but a 2017 analysis still found actual statistics to be far from the stated goals.

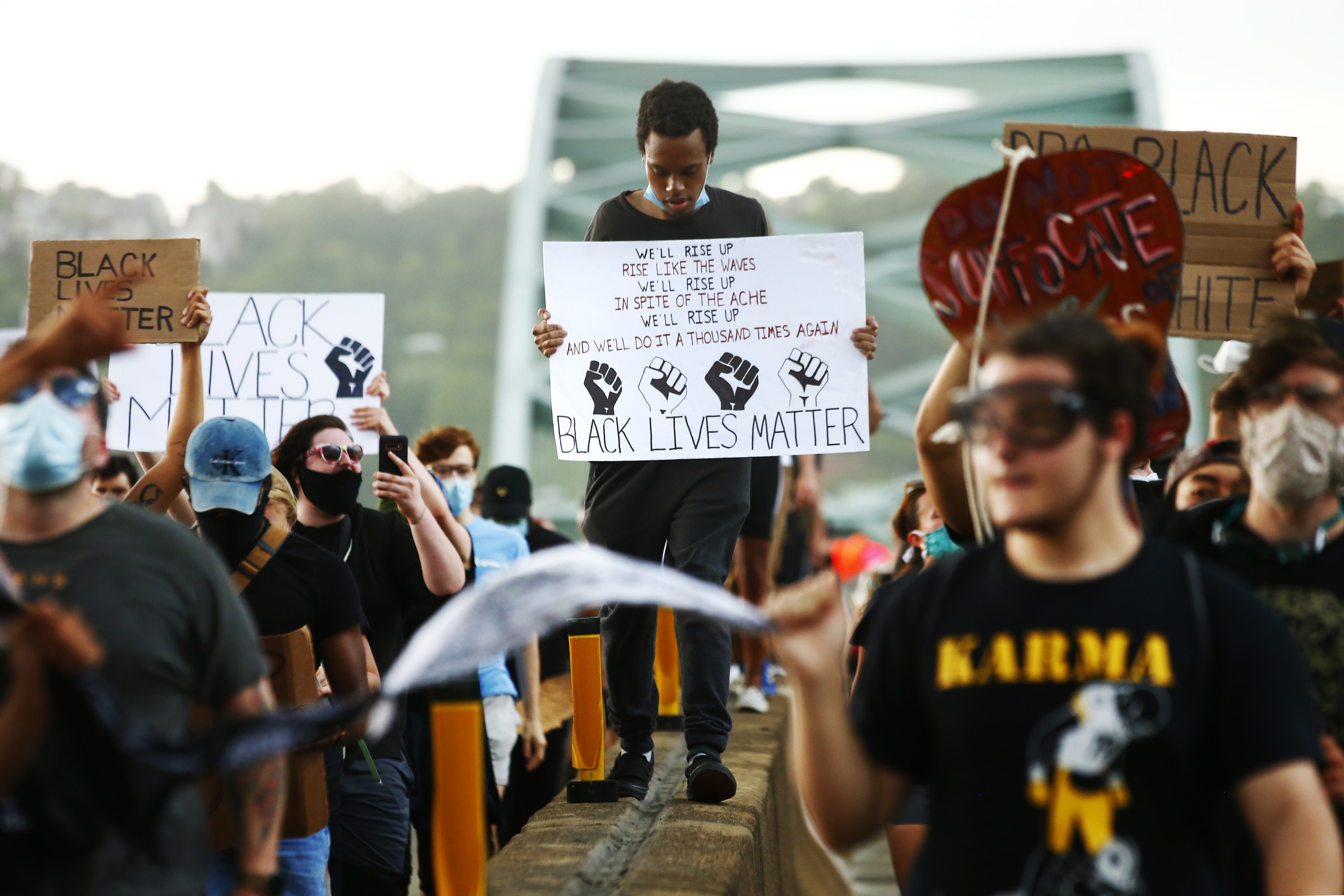

Photo of a Black Lives Matter Protest in 2020 by Jared Wickerham for the Pittsburgh City Paper. (Source)

Photo of a Black Lives Matter Protest in 2020 by Jared Wickerham for the Pittsburgh City Paper. (Source)

Even as newsrooms slowly become more diverse, professional journalistic structures and practices are still major obstacles to fully addressing the profession’s preservation of whiteness and exclusivity. Just one example of this occurred at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in June of 2020, when editors at the paper prevented two of their top reporters, both of whom are Black, from reporting on the Black Lives Matter protests in Pittsburgh. This occurred in part because Alexis Johnson, one of the excluded reporters, shared a tweet of her own personal commentary on the protests that she felt was funny and thought-provoking. Despite no staff social media policy, the upper-level management rejected her multiple story pitches and eventually outright excluded her from reporting on the protests because they felt that further coverage could be seen as biased and cause “the credibility of the newsroom [to] be questioned.”

Objectivity and neutrality, which have long been core tenants of journalistic practice, have contributed to maintaining white perspectives in professional journalism as the only form of “objective” and “neutral” reporting. Ultimately, this means that reporting that is not racially informed is considered properly neutral and objective, furthermore promoting the neoliberal ideal of color-blindness. In contrast, racially informed reporting, reporting from journalists of color, and stories for audiences of color are viewed as biased storytelling or relegated to niche media.

The dedication to “objectivity” in reporting is just one example of centering white perspectives in journalism; multiple publications have admitted to producing overtly racist content and enacting discriminatory business practices in both the past and present.

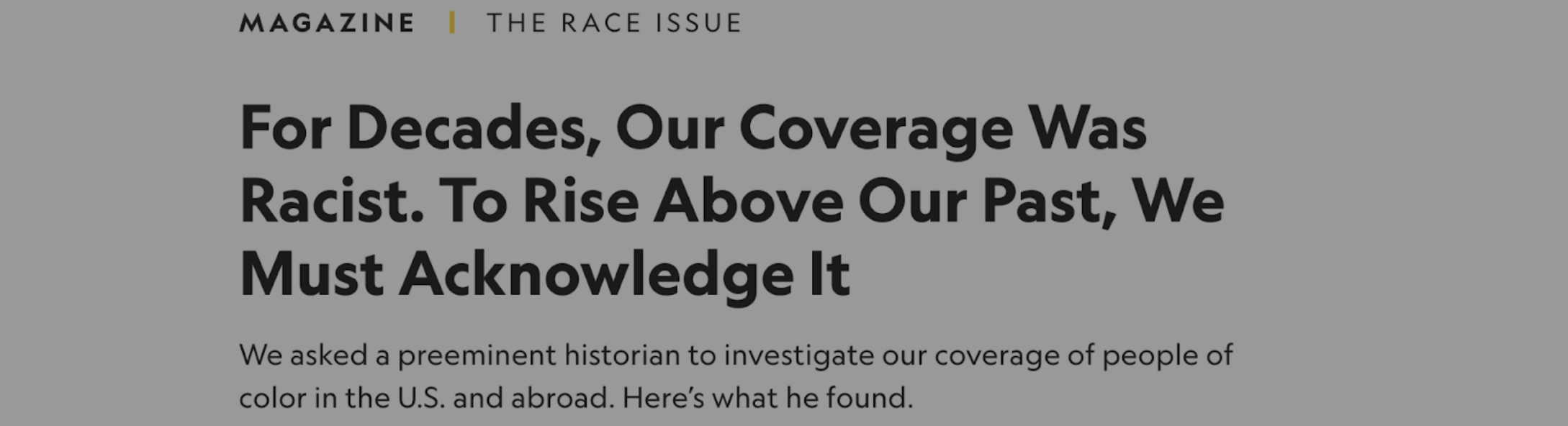

Screenshot from Editor-in-Chief Goldberg’s 2018 letter about National Geographic’s history. (Source)

Screenshot from Editor-in-Chief Goldberg’s 2018 letter about National Geographic’s history. (Source)

National Geographic began their own racial reckoning in 2018, when Susan Goldberg, the magazine’s first female Editor-in-Chief, acknowledged the publication’s problematic past of disregarding American people of color and pushing stereotypes of exotic and primitive native people around the world. In the years following, the magazine hired more women, publicly covered LGBTQ+ issues, and added two women of color to their executive team.

National Geographic recommitted to this work during the summer of 2020, and staffers say there have been improvements but more are needed, structurally and socially. Lower level staffers felt that changes in coverage, content, and workplace culture were lacking and that their pushback was met with resistance from upper-level leaders.

Across many media organizations, lower-level staffers have felt the added pressure to advocate for these changes and were sometimes met with dismissal, leading to intense stress and a complicated relationship with the brand and their work. Unfortunately, vowing to value and prioritize people of color and then continuing to ignore or tokenize their ideas and careers is not uncommon, as an investigation by the Nieman Lab found in newsrooms and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) positions at publications across the country. These reporters shared anecdotes which included feeling overlooked, overworked and emotionally drained, in addition to being stifled by the editing process and limited in their ability to adequately call out instances of racism and sexism.

Varying Paths within One Publisher

An interesting contrast exists between the responses from two prominent Condé Nast publications: Bon Appétit and Vanity Fair. In late May of 2020, Adam Rapoport, then-Editor-in-Chief of Bon Appétit, wrote a column addressing the murder of George Floyd and affirming the magazine’s editorial mission and values of justice; just a few weeks later he resigned when a picture surfaced of him in brownface. Following his resignation, staffers opened up about the toxic work environment at Bon Appétit, where BIPOC staffers were taken advantage of, underpaid, and mistreated. Assistant Food Editor Sohla El-Waylly shared that she had been paraded as a token of diversity in Bon Appétit’s popular Test Kitchen videos, but her appearances were not compensated, unlike her white coworkers. In addition, Bon Appétit’s content contributed to the overall food-industry trends of white-washing. This is exemplified by instances of white cooks and creators taking credit for and profiting off of diverse recipes that are painted as “trendy,” when they are not outright ignored or discredited.

Screenshot of the web edition of Vanity Fair’s September 2020 edition. (source)

Screenshot of the web edition of Vanity Fair’s September 2020 edition. (source)

Though institutional issues at Condé Nast remind us workplace and content discrimination was most certainly pervasive throughout the company, some individual publications fared better than others. Vanity Fair has made strides in inclusive coverage since Radhika Jones took over as Editor-in-Chief in 2017, making her one of the only top editors of color in Condé Nast’s history. Immediately after taking control, Jones championed increased content featuring people of color, especially as cover stars. Following the 2020 summer of Black Lives Matter protests sparked by instances of police violence against unarmed Black people including George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, Ms. Jones assisted in the curation of an issue that highlighted Black stories and voices. The September edition, which is annually one of the most important issues, was guest edited by best-selling and highly-revered author Ta-Nehisi Coates and featured a portrait of Breonna Taylor on the cover. The issue highlighted content from multiple Black writers and creators, sharing stories of everything from the Black Lives Matter and abolition movements to the realities of unpaid college football. This edition of the magazine, titled “The Great Fire,” exemplifies moral solidarity in journalism. Moral solidarity in the news portrays marginalized people as “subjects of justice” with personal and political agency, and requires comparatively more privileged groups of people to amplify the experiences, desires, and solutions put forth by the affected communities.

As part of Condé Nast’s company-wide reckoning, they pledged to incorporate more inclusive hiring practices to diversify their staff at all levels, including editorial. As part of their accountability goals, Condé Nast committed to releasing an annual Diversity & Inclusion Report, which includes statistics on new-hire, editorial, and overall staff diversity. In 2021, 32% of all U.S. staffers identified as people of color (compared to approximately 28% in 2020) and 41% of new hires were people of color (compared to approximately 38% in 2020). However, as of 2021, 78% of Senior Leadership positions were held by white people, up from 77% in 2020. These numbers unfortunately are in accordance with the anecdotal struggles from reporters in newsrooms across the country who feel much of the work towards inclusivity rests on the shoulders of staffers of color tasked with standing up to upper management.

Major Challenges Remain for Media Companies

While these staffing numbers are just a piece of the overall picture, they give an indication of the significant obstacles still in place that may prevent a truly inclusive workplace and perspective shift at Condé Nast and newsrooms around the country. As we move towards a new era of journalism, the role of apology letters and declarations of inclusivity are still unclear. Idealistic narratives of American progress promote the idea of a society that naturally trends towards justice and equity. However, this narrative perpetuates an optimistic view of slow but consistent progress that can minimize the severity and urgency of current racial inequities.

As Condé Nast’s annual Diversity & Inclusion Report gives us a statistical window to the hiring practices and future diversification within the organization, the parallel issue of content diversity is just as important to study. A recent piece by The Hollywood Reporter highlighted the new wave of POC editors at various publications across the country, discussing the challenges, responses, and ways that they have banded together to promote long term change in their newsrooms. Across the country, journalists at all staff levels have shown a dedication to racial equity in media, inspiring hope about the direction of the profession despite the significant progress left to be made. The racial reckoning of 2020 catalyzed a long-overdue reflection and restructuring process in professional journalism which will set industry standards for years to come. As we move forward, true progress towards racial equity in the media will require pay and benefits transparency, comprehensive shifts in internal policy, a new definition of journalistic objectivity, and diligence at all staff levels.