I was honored to attend and speak at a recent UN event about how AI might be reshaping the contours of human security: Human Security at 30: New Security and Development Horizons in the Artificial Intelligence Age (hosted by the UN Human Development Report Office). It was fascinating to bring my experience with participatory AI into this setting and it’s focus on human security, which was new to me. It was even more intriguing to be cast as an “AI expert” in the room of development experts, many of them working on next year’s Human Development Report. I left feeling both buoyed by the amazing work and energy, but also dismayed by the feeling of inevitability in the room, and associated embracing of corporate AI narratives. New technologies we are calling “AI” pose ongoing and future threats to human security, but we get to decide who, how, and for what these tools are built and used; we can’t cede the space to Big Tech’s corporate cloud solutions. I want to share some reflections on the public morning session in this blog post.

Pedro Conceição, head of the UN Development Report Office, introducing the event

Pedro Conceição, head of the UN Development Report Office, introducing the event

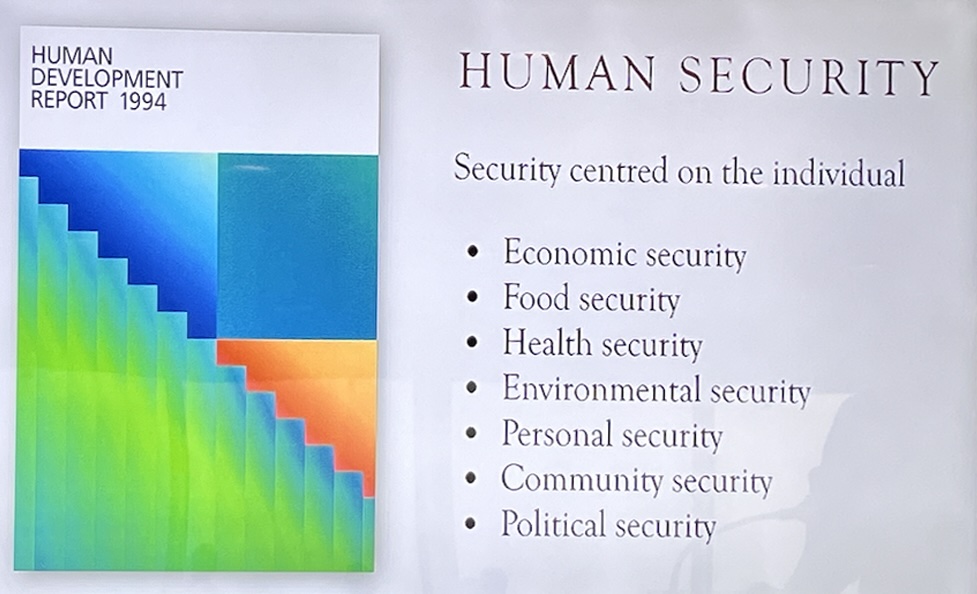

The event was one in a series of “listening session” style events that inform the production of the annual UN Human Development Report. Many of these center concepts from “human security”, which focuses on protecting individuals (rather than states) from threats such as poverty, inequality, and environmental risks. The idea emerged in the 1990s, driven by definitions from Japan and Canada. Unlike state-level security, which prioritizes borders and military strength, human security emphasizes freedom from fear, want, and indignity, tackling root causes of insecurity, and more. The key idea is that a people-centered approach is essential in addressing global challenges that don’t stop at national boundaries; a category that more and more of our growing challenges fit into, hence the event on human security and AI.

Existential Risks in the AI Age

Toby Ord, senior researcher at Oxford University and author of The Precipice, kicked off the first panel with a sobering keynote focused on the question of AI as an existential risk to our species. He argued that humanity’s greatest risks stem not from natural forces but from our own tools. Ord stressed that AI development is accelerating far beyond our readiness to manage its consequences. To him, industry leaders and international figures have sounded the alarm, yet policy and public discourse lag behind. For Ord, safeguarding the future necessitates treating global AI regulation as a public good—a commitment as enduring and robust as the international frameworks governing nuclear weapons or climate change. I found his commentary to be provocative, because so often I find the “existential threat” narrative around AI to be a corporate smoke-screen that pushes attention away from concrete ongoing harms. I’m not worried about robot overloads controlling my fate; I’m worried about encoded discrimination in decision making, environment harms and exacerbation of power scarcity, impacts of the rampant spread of generated disinformation, and so on.

Tory Ord’s summary of human security

Tory Ord’s summary of human security

The associated panel of experts highlighted AI’s dual potential to empower and endanger, emphasizing the urgent need for ethical governance and equitable development. Laura Chinchilla, former President of Costa Rica, noted the rise of AI-enabled cybercrimes like phishing and fraud, which have outpaced legal frameworks, and stressed the importance of ethical standards and human rights education to mitigate these harms. Turhan Saleh (UNDP) framed AI within a rapidly evolving global risk landscape, cautioning that while its benefits remain hypothetical and unequally distributed, its costs are already exacerbating inequalities. His arguments strongly reflected some of my own short-term concerns and priorities in this space. Daniella Darlington, a responsible AI advocate, called for investments in data governance, community stewardship, and workforce education in the Global South. She pointed to barriers like limited computational resources, insufficient training, and low public trust—challenges that align with my perspective on addressing present risks rather than speculating on future scenarios.

Restoring Trust in an Age of Worry

The second keynote was from Prof. Rita Singh (Carnegie Mellon University), who took a researcher’s lens to the opportunities and unsolved problems of AI development. Singh works on advanced tools that use voice in numerous ways, including profiling. She called for intentional, human-centered design principles that prioritize societal needs over purely technical ambitions, including calls for society to encode incredibly complex things such as social norms and ethical behaviors into constructs that AI researchers could then implement. I personally found this take quite challenging to engage with, full of language I’d label at first glance as techno-centrist and reductivist. Encode ethical rules in some machine understandable way is incredibly complex and daunting, hardly a simple pre-condition to check-off on the way to building ethical bots.

Others on the panel shared how AI is increasingly embedded in everyday life, leading to concerns about disinformation, job displacement, and online safety. These feelings of distress and distrust are pervasive, with six out of seven people worldwide reporting insecurity in their lives. The discussion explored how the human security framework, which emphasizes freedom from fear, want, and indignity, could be reimagined to address AI’s challenges and restore trust.

I was a participant on this panel, asked to address how citizens and community-based initiatives in data collection and technology development might help restore trust and enhance agency. I emphasized that AI’s future is not inevitable—we have the power to choose what to build. By fostering empowerment and ownership in technology development, we can shift the narrative of insecurity toward one of control and agency. Technology systems are inherently socio-technical, and AI is often a marketing term masking this complexity. Centering local expertise and engaging stakeholders in problem definition is crucial for creating public-interest technologies that address meaningful challenges in particpatory and empowering ways.

I shared examples from the Counterdata Network, where we work withcivil society organizations to develop AI tools for monitoring news flows that surface and document human rights violations. This model demonstrates that AI doesn’t need to rely solely on cloud computing solutions in the Global North; it can be localized and aligned with grassroots needs and capacities. I sought to echo and amplify what I learned from my colleague Alessandra Jungs de Almeida on rethinking “securitization” through feminist perspectives, framing security not as abstract defense but as safeguarding the lives and dignity of women and girls. This reframing, I argued, could profoundly reshape how we approach AI’s role in supporting or threatening human security.

Towards Equitable AI Futures

The event underscored AI’s power to exacerbate global divides if left unregulated. It risks deepening inequalities between the Global North and South, with wealthier nations monopolizing AI’s benefits while poorer nations grapple with its harms. Human security, as defined over the past three decades, must now adapt to include AI’s promise and perils. From empowering women in AI development to addressing the digital gender divide and ensuring equitable access to AI resources, the path forward demands global solidarity and a renewed commitment to ethical governance.

The juncture that this event focused on offers an opportunity: to redefine security not as freedom from fear alone, but as the ability to thrive in an interconnected, AI-driven world. Will we seize the opportunity to take ownership of who gets to build AI, for which purposes, and with what processes? I was left believing that a human security-inspired approach to AI demands that of us.