The University of Bologna graciously hosted csv,conf,v9 in Palazzo Malvezzi. Accordion music drifted in through the windows while we gathered, echoing the mix of technical innovation and creative application that folks shared. Speakers from around the world shared how they’re using data not just to inform, but to transform communities. Here are gently editing notes from the sessions I attended (edited with some help from AI); any errors are probably my fault.

Photo of all the attendees at csv,conf,v9 (source: John Chodacki)

Photo of all the attendees at csv,conf,v9 (source: John Chodacki)

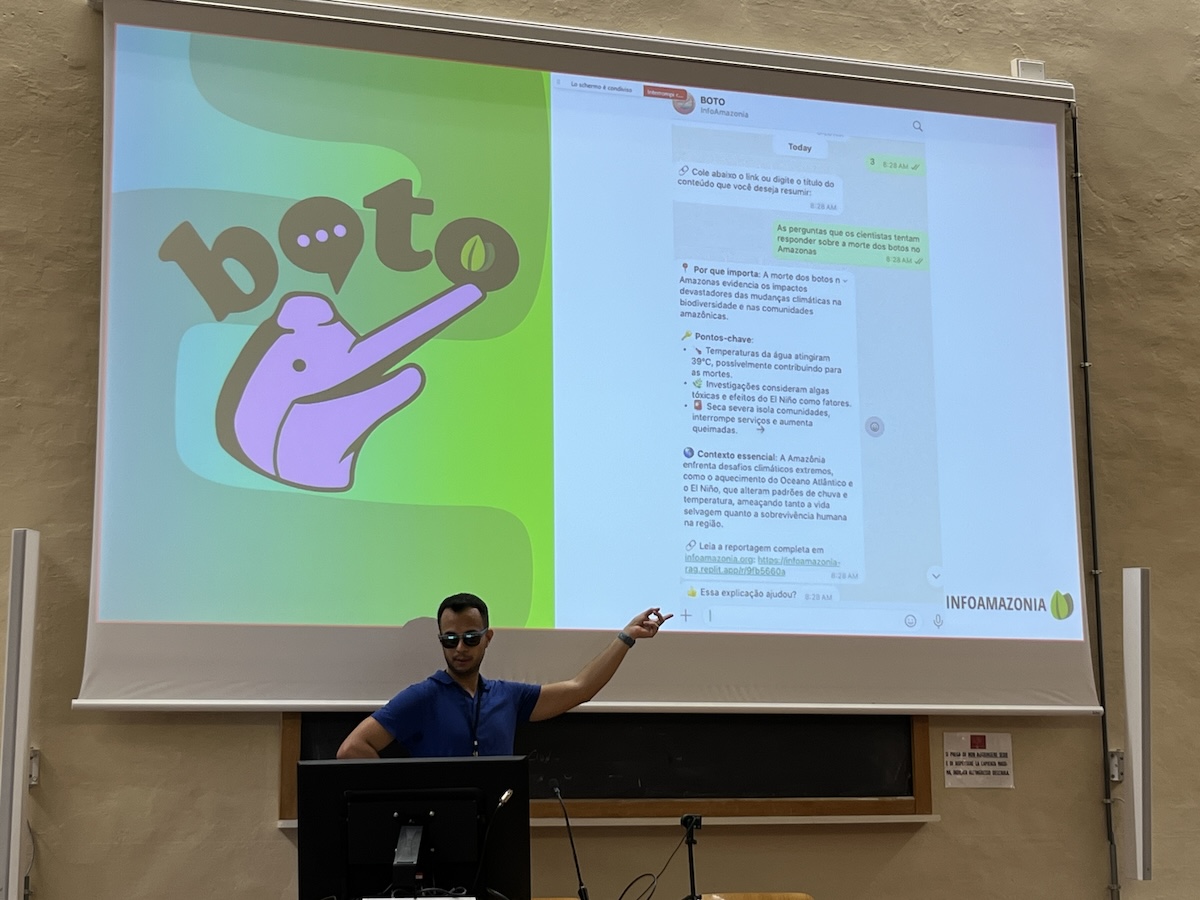

Filling Information Voids with Chatbots: Using LLMs on WhatsApp for News Access

Mathias Felipe (he/him), InfoAmazonia

In the Amazon forest, communities often face critical information voids around environmental issues, while relying heavily on WhatsApp as their main communication platform. This talk presents BOTO, an open-source chatbot developed by InfoAmazonia that delivers localized, thematic environmental information—such as deforestation alerts and wildfires—through WhatsApp. Powered by Large Language Models (LLMs) and designed with a low-bandwidth architecture, BOTO aims to make local news information more accessible in under-served areas. In this talk, we’ll discuss how BOTO was created with participatory design to empower communities, bridge information gaps, and put news directly in the hands of those who need it most.

The most striking thing about BOTO isn’t its technical architecture, others are also exploring WhatsApp Business API integration with RAG-based article search; it’s how InfoAmazonia approached the design process. Focus groups with different indigenous communities shaped every decision, from interface choices to content summaries. The result? A system where people can select their region and themes, then receive data summaries and links directly to their phones.

Felipe emphasized something crucial: their audience doesn’t have a problem with chatbots. The hesitation comes from outside assumptions about what “non-technical users” want. When you actually ask communities what they need, the solutions become clearer. BOTO soft-launched recently with official rollout planned for next month, sponsored by ICFJ. The real test will be sustained engagement, but the co-design foundation suggests they’re building something people actually want to use.

Blazing Fast Automagical Metadata

Joel Natividad

With the pervasiveness of low quality, low resolution metadata in existing Data Catalogs, and new metadata standards like DCAT3 and Croissant demanding even more FAIR metadata, how do you make it easier for Data Stewards to maintain High Quality Data Catalogs?

Natividad’s (from datHere) talk hit on every data steward’s nightmare: the metadata maintenance burden. New standards like DCAT3 and Croissant (for machine learning) demand even richer metadata: properties, data dictionaries, summary stats, frequency tables. The solution? Flip the workflow. Instead of forcing metadata entry before data upload, let people upload first and generate suggested metadata automatically. Their qsv and describegpt tools infer data dictionaries, descriptions, and 40+ summary stats. It creates a “data steward in-the-loop” approach—human oversight with automated assistance.

Most intriguingly, they’re moving toward “chat with your catalog”—custom chatbots that can surface relevant CKAN datasets when answering questions. It’s RAG applied to data discovery, potentially transforming how people find and use datasets that are published and publicly available.

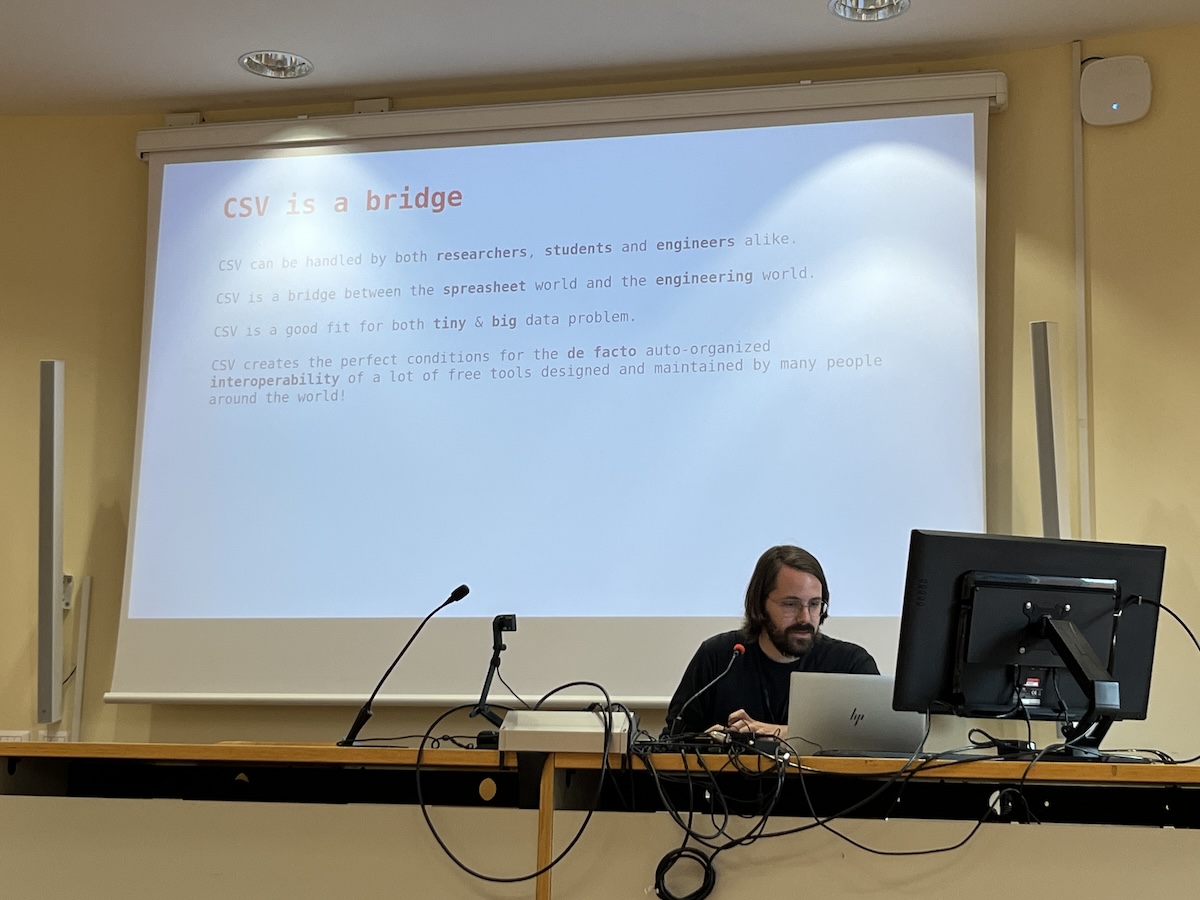

Building CSV-powered tools for social sciences

Guillaume Plique (he/him), médialabSciencesPo, Paris

CSV is ubiquitous in social sciences and in the humanities. CSV data is indeed the perfect bridge between social scientists, accustomed to dealing with tabular data, and research engineers needing to process the same data. That is why SciencesPo’s médialab has been building many of its Open-Source tools around CSV files, from well-designed web apps such as Table2Net to convert tabular data into graph data, down to powerful CLI tools such as minet to collect data from the web or xan to process tabular data using constrained resources.

Plique delivered a love letter to CSV. His argument is compelling: CSV is affordable, understandable, and free. It functions as a bridge between researchers, students, and engineers. It doesn’t require complex compute resources and naturally encourages data sobriety. The médialab’s tool ecosystem is impressive—table2net for web-based CSV-to-graph conversion, takoyaki for clustering CSV data to find clerical errors, minet for CLI-based CSV processing, and xan for visualization. All built on the principle that tabular data is inherently more comprehensible than JSON hierarchies. His closing advice: “If you need random access, use SQLite. Otherwise, CSV.” It’s a reminder that sometimes the simplest tools are the most durable—you’ll still be able to open a CSV file in 50 years.

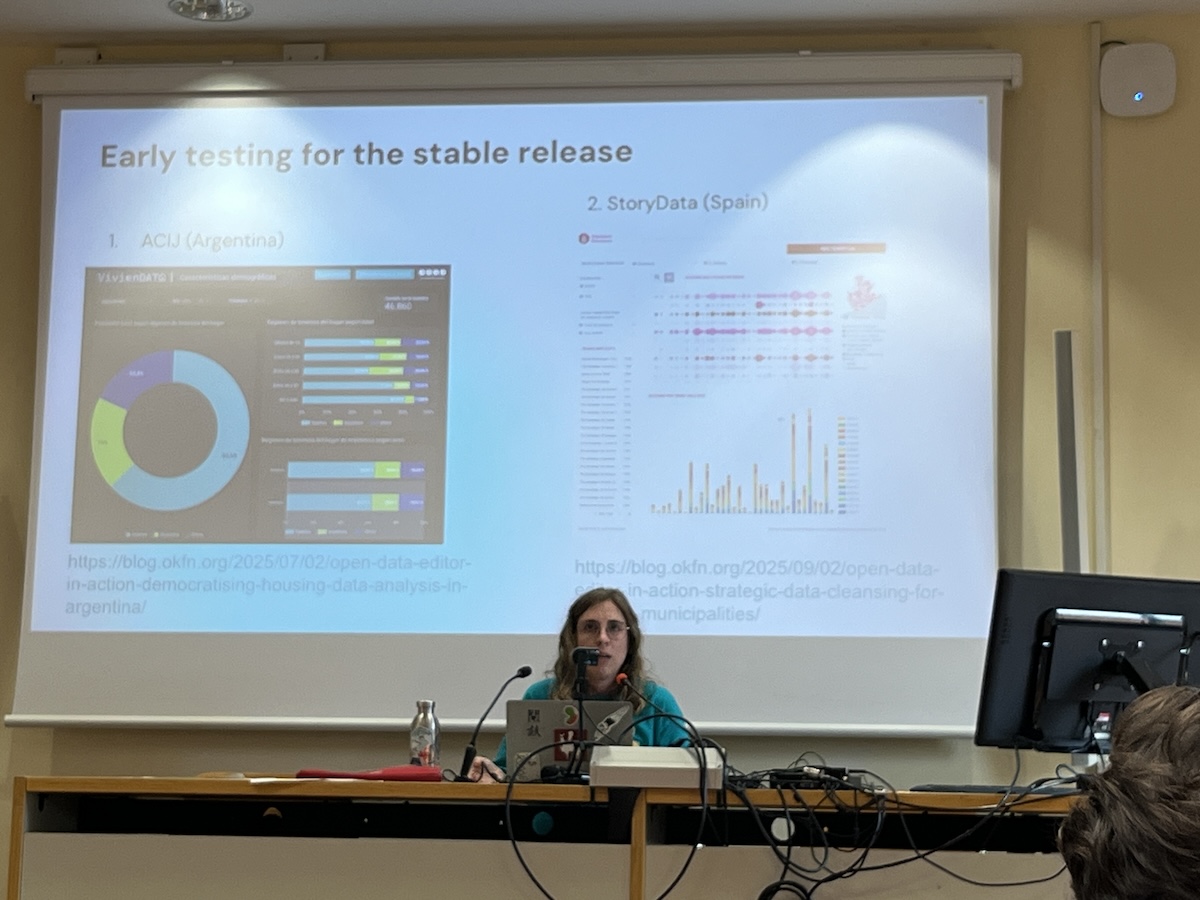

Keynote: Developing tech with community: the example of Open Data Editor

Sara Petti, Open Knowledge Foundation

Open Data Editor is a desktop application specifically designed to help people detect errors in tables. It has been developed in constant interaction with the community from a very early stage. These interactions helped us understand what was really helping the community and what not, and especially made us aware of how much the use of such a tool could actually be helpful in increasing data literacy.

Petti’s keynote was a masterclass in community-centered design. OKFN initially tried to build “an app to do it all”—review data, prepare it, map it, write articles. The scope was overwhelming and misaligned with user needs. The breakthrough came through extended pilot testing with organizations like ACIJ in Argentina and StoryData in Spain. This led to dramatic simplification and focus. The second round of pilots with five different organizational types revealed something crucial: researchers worried about changing metadata, navigation and design were hugely impactful, and people don’t read documentation.

Key lessons that resonated: language matters enormously (“validation,” “execute” carry technical baggage), there’s only so much you can do to make highly technical tasks accessible, and many challenges are fundamentally non-technical. Most importantly—iterate based on feedback, keep things simple, and don’t be confused by the latest tech. The project pivoted from React to a more sustainable framework, emphasizing the importance of maintainable code over popular technologies.

Democratizing data: data literacy for community action

Emily Zoe Mann (she/her/hers), University of South Florida Libraries

This presentation will share the results of Data Literacy for Community Action, a year-long pilot in the community of St. Petersburg, Florida, USA that provided data literacy to non-profit groups and interested members of the community, with a focus on using local data sets and data related to social determinants of health.

Mann’s project exemplifies academic-community collaboration done right. The partnership between University of South Florida, the public library system, and a philanthropic health equity organization created something none could achieve alone. The workshop structure was brilliantly simple: introduce a concept, share a local dataset demonstrating it, bring in a local person to discuss real-world application, then run group activities. Her red tide sonification example from South Florida shows how hyperlocal data becomes immediately relevant when paired with familiar environmental experiences.

One insight that stood out: attendees came with vastly different question types, from basic to nuanced. Mann’s library background prepared her for meeting people at all skill levels, but it reinforced how “data literacy” isn’t a single skill—it’s a spectrum of capabilities that communities develop over time. The flexibility lesson is crucial for similar pilots: stay responsive to what people actually need rather than predetermined curricula.

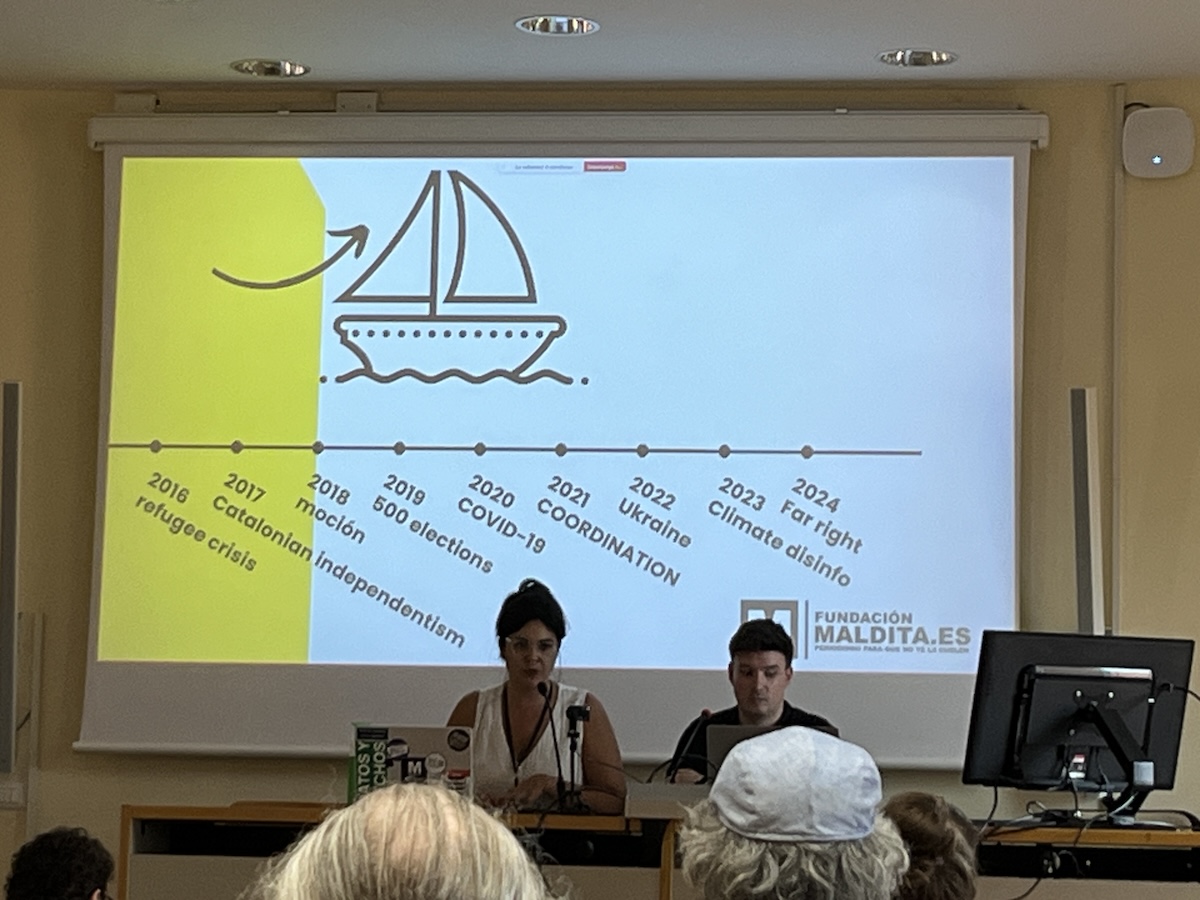

Keynote: Clara Jiménez & David Fernández Sancho

Maldita.es Foundation

Clara Jiménez Cruz is the co-founder and CEO of the Maldita.es Foundation, a leading organization in the fight against misinformation… David Fernández is the current CTO of the Maldita.es Foundation, where he leads the development of innovative digital tools to combat disinformation.

This keynote hit hardest, perhaps because of recent events. Jiménez and Fernández positioned disinformation not as isolated false information, but as structured narratives—emotionally engaging, rationally grounded, amplified by trusted figures, global in scope. Their Valencia floods case study was chilling: the same narrative emerging simultaneously from Russian sources, far-right groups, and anti-vaxxers, all attacking institutional trust. The message was consistent: “You can’t trust government, trust me.”

Their AI-assisted approach uses Wikidata entity extraction to cluster claims, with human-in-the-loop narrative association. They’re tracking 600+ claims monthly—a scale that demands automation while recognizing AI’s limitations in understanding social context.

The most powerful moment was Jiménez’s declaration: “data as a means of resistance.” In an environment where “the internet is becoming more dangerous on purpose,” systematic documentation and analysis of disinformation patterns becomes a form of civic defense.

Data without borders: Straight out of spreadsheets and into the streets

Michael Brenner (He/Him/His), Data4Change

At Data4Change, we work with communities around the world to explore how data can be collected, understood and shared in radically different ways. This talk takes you through a series of surprising, community-led projects that didn’t begin with data, but with burning questions our community partners wanted to find answers to.

Brenner’s examples were extraordinary—from addressing intimate partner violence in Uganda’s LGBTQ community, to flute music rendering Ethiopian census data audible to the blind. Each project started not with data, but with burning community questions. I mention many of them in my Community Data book.

The data murals project with Haki Data Lab in Mathare particularly resonated. Rather than imposing external visualization methods, they recognized murals as a standard local communication mode, then created input visualization murals with string and stencils. The “power portraits” methodology for the Equal Victims project was brilliant—co-created visual representations that function simultaneously as art and data points about lived experience, avoiding retraumatization while enabling systematic documentation.

Brenner’s language shift is important: moving from “data literate” toward “data curious, data critical, and data confident.” It reframes the relationship from deficit-based (lacking literacy) to asset-based (developing capabilities).

Keynote: Fifteen Years into the Open Data Movement

Giorgia Lodi & Andrea Borruso

Fifteen years into the open data movement, we take the stage as an unusual duo to reflect, provoke, and laugh about where we’ve landed. A dialogue, shaped by friendship, a few successes, many failures, and a bit of fun—think less keynote, more late-night talk show.

This closing keynote was part celebration, part wake-up call. Lodi and Borruso’s Italian open data examples were both hilarious and heartbreaking—ministry electric charging station data published with beautiful graphs but completely locked down, forcing community scraping to make it actually useful. Their analysis cuts deep: following the letter of the law isn’t enough when datasets lack description, remain readable only by specialists, or simply don’t exist (particularly around gender-based violence). Communities get pushed out by technicalities, formalism, and missing data.

A case study about electric car data exemplifies the problem—officially “open” data published as unusable pivot tables instead of raw, machine-readable records. When the ministry finally released proper data, it came with semicolon separators and complete messiness. But their vector geography data example shows what’s possible: despite delivery delays and nested zip file complexity, raw land ownership data triggered new software, plugins, and services precisely because it was genuinely machine-readable.

Their conclusion resonated throughout the conference: exploit technology to support data management, think about machine-to-machine AND machine-to-human AND machine-to-community interfaces, and recognize that technical solutions alone can’t address fundamentally social challenges.

Reflections: Data as Community Practice

Walking through Bologna after two days of talks, I kept thinking about the accordion player who inadvertantly soundtracked the opening day. There’s something fitting about that mix of structure and improvisation, tradition and innovation. These presentations collectively argue for a fundamental shift in how we approach data work in and with community. We must shift from extraction to engagement, from literacy deficits to community assets, from technical solutions to socio-technical systems. Whether it’s BOTO’s co-designed news delivery, Data4Change’s participatory data projects, or Open Data Editor’s community-driven development, the most compelling projects start with community questions rather than data capabilities.

I gave a keynote related to my _Community Data_ book (source: Marco Cortella)

I gave a keynote related to my _Community Data_ book (source: Marco Cortella)

The CSV theme threading through many talks isn’t just about file formats—it’s about accessibility, sustainability, and democratic participation in data practices. In a world increasingly dominated by complex AI systems and proprietary platforms, there’s something radical about insisting that the most important data work can happen with simple, open, maintainable tools. As disinformation accelerates and institutional trust erodes, these community-centered data practices feel more urgent than ever. The question isn’t just how we make data more accessible, but how we make data work serve community needs rather than institutional convenience.