Organizations across the news industry are exploring ways to use generative AI to support their storytelling (many shared on this very blog). A growing trend is to use these new tools on the other end of the production cycle, to support content audits that assess a large set of stories against the mission and goals of your newsroom. With Meg Heckman and Liz Hadjis, I conducted a test of this approach in partnership with a hyper-local outlet (The Scope Boston), and I want to share some of our methods and higher-level critical questions. Hopefully these help you come up with a thoughtful strategy for how you might integrate AI-assisted content auditing into your editorial workflows.

More and more newsrooms are performing content audits and publishing them online.

More and more newsrooms are performing content audits and publishing them online.

A growing number of newsrooms are taking on content audits, from the Philadelphia Inquirer to the City NYC, measuring alignment between their stories and editorial goals. The Scope’s audit was motivated by their mission to highlight under covered places and peoples in Boston. They wanted to measure whether their content matched that goal by analyzing (1) which locations got the most coverage, (2) what topics dominated their reporting, and (3) whose voices were most quoted.

What We Did, and What We Found

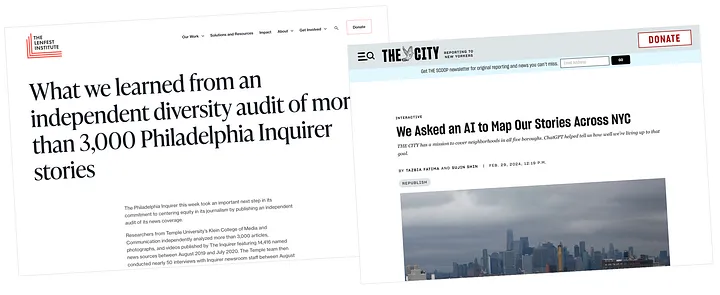

We worked with the Scope’s editor to gather all their content and then report back on those three guiding questions: places, topics, and quotes. The first two were relatively easy to do with off-the-shelf open-source technologies for extracting places mentioned in text and assigning classic news topics to a story. The third was harder, because we found no ready-to-use tool for news articles that could extract quotes, attribute them to speakers, and tell us which pronoun was used about their speaker (so we could determine their gender ethically). For that one we turned to generative AI and after iterating on prompts we were surprised to see that it performed quite well.

A block diagram of our prototype technology pipeline.

A block diagram of our prototype technology pipeline.

As with any project, data cleaning took a big chunk of the time. However, since we started with a machine-readable XML export from the Wordpress-hosted site the cleaning was mostly on the results. For instance, we had to filter geographic places for only local neighborhoods and do things like convert “Jamaica” into “Jamaica Plain”. For the quotes, because we used generative AI, we had to validate that each and every quote was actually from the story, and that the attributed speaker’s name was also in the text. To my surprise ChatGPT didn’t invent any quotes or speakers and only ended up costing about USD $6 in total (via API calls to their “gpt-3.5-turbo” model). See the pre-print we presented at AEJMC earlier this year for details on the prompts and related methods.

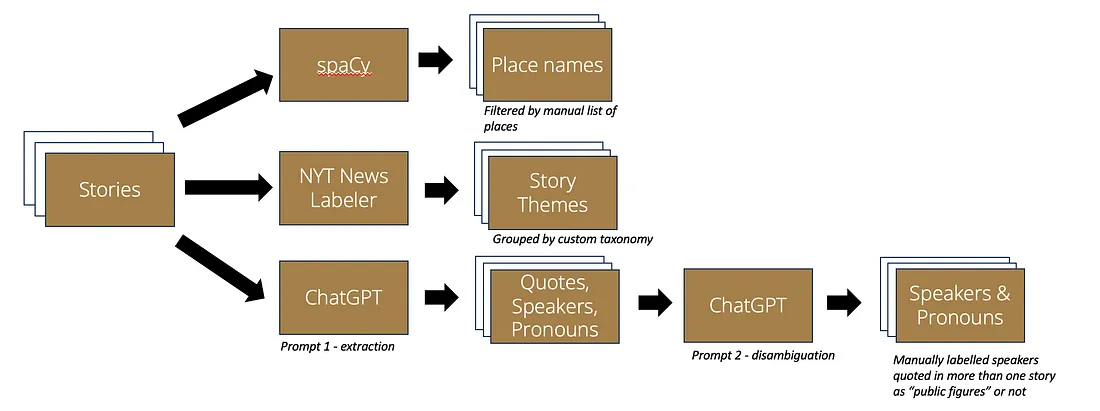

At a high level, we found some validation for the Scope’s existing practices and some opportunities for improvement in line with the mission statement. Geographically, coverage was dispersed across the city and the neighborhoods editors hoped to focus on. However, while some Boston neighborhoods, like Mission Hill (17% of stories), were covered extensively, other areas like Mattapan and Roxbury received less attention (1% each) despite being very close to the institution that operates the publication (Northeastern University).

The Boston neighborhoods covered most often in stories. Longer bars mean more stories mentioned that place.

The Boston neighborhoods covered most often in stories. Longer bars mean more stories mentioned that place.

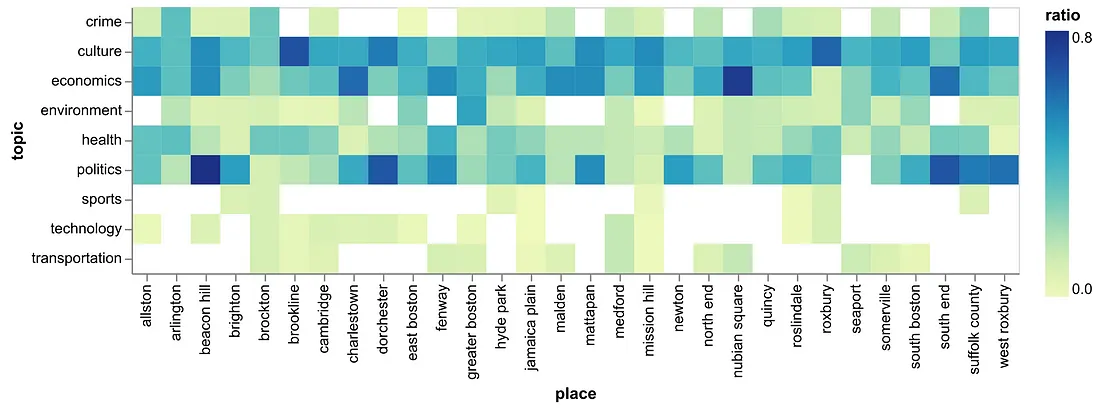

In terms of topics, culture (26% of stories), politics (18%), and economics (17%) dominated The Scope’s coverage, which made sense given their mission. However, we found that other issues the editors deemed important like transportation (2%) and technology (<1%) received little attention. This was especially true when we dug into the topics covered in neighborhoods; note the absence of transportation coverage in Mattapan, Quincy, and Roxbury despite it being an important local issue.

A heatmap-style diagram showing how much each topic was covered in each neighborhood. A darker blue square means more coverage of that topic in that place. A blank square means no coverage.

A heatmap-style diagram showing how much each topic was covered in each neighborhood. A darker blue square means more coverage of that topic in that place. A blank square means no coverage.

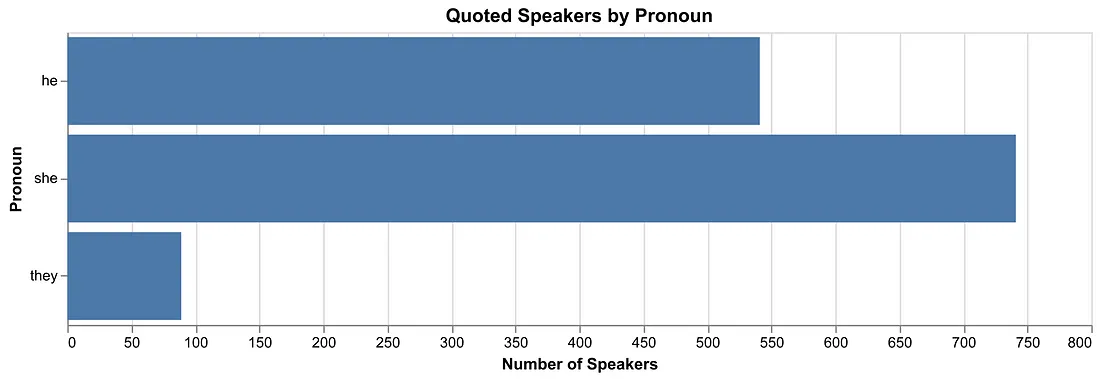

For quotes, speakers were identified by “she” (57%) more than “he” (38%), perhaps because many of its reporters identify as women. In addition, very few of the top quoted people were politicians or other public figures. Just 37% of those quoted overall fit into this “social elites” category. These findings counter results from research across mainstream media sources.

A chart showing quoted speaker gender based on the pronoun most-often used to refer to them in the stories. Bigger bars mean more unique speakers were referred to with that pronoun.

A chart showing quoted speaker gender based on the pronoun most-often used to refer to them in the stories. Bigger bars mean more unique speakers were referred to with that pronoun.

These results matched some of what the publication suspected, but also introduced some surprises and ideas for changes to consider for the upcoming year of coverage. You can read our full academic paper from the 2024 Computation + Journalism Symposium to see more detailed results about these three approaches we took in our content audit.

What You Might Want to Try

Taking on a content audit might seem daunting, but with just a few days of work a data scientist could produce a first draft. We’re hoping to make that even easier by finding partners and funding to build a web-based toolkit others could use.

In the meantime, if you do want to get started on this sort of thing, there are some key preparatory and strategic conversations and tasks that you should take on. First, before choosing any tools you need to define what you want to measure and ensure it is in alignment with your mission. Local newsrooms have a geographic focus, so that is kind of an obvious choice. Beyond that, what kind of representation do you care about? Linguistic? Quotes? Identities? Organizations?

Second, when you’re ready to do some technical work try to choose well-validated off-the-shelf machine learning tools before diving into generative AI systems like ChatGPT (more on this below). Established tools are often already evaluated and robust from prior studies and use. They also create reproducible results, unlike this new batch of generative LLM tools that can sometimes make things up.

Third, once you have data, be sure to take the time to interpret the findings with your team and broader community. The data you find isn’t going to be perfect but can reveal patterns that tell you something about your coverage and might suggest changes you could make. If certain populations, places, or topics are consistently underrepresented, make a plan to address this in future reporting.

Finally, make a commitment to regularly audit your content every year or so and publish it publicly to hold yourself to account. Integrating this kind of process into your annual workflow is the only way to create meaningful results and change over time.

Be a Critical Technology User

I could end this write-up here, but I think there’s an important reflection about technology that also needs to be addressed. Chat-based generative AI tools feel like a magical solution to using advanced computer-based language analysis approaches, but I encourage you to be a skeptical consumer in the face of the massive hype around them. Note that we only used the ChatGPT API where we could find no other solution. I have three main reasons why I think this stuff should be a tool of last resort: hidden costs, relational risk, and accuracy.

To start with, the energy costs of using these tools are massive. The power needed to create generative AI models and run them is unsustainable and exacerbates existing ecological disparities. The now-famous “Stochastic Papers” paper from Bender, et al documents this in depth. Power consumption needs are driving a massive race between companies to secure energy supplies for their server farms in a world already suffering from scarcity. Many alternative non-generative machine learning models that have been around for a while can run on your laptop computer, take far less power to train, and produce accurate and usable results for many audit-related tasks.

On top of that consider the history of Big Tech as an untrustworthy partner to newsrooms. Remember Google’s AMP? The Facebook-driven pivot to video? Suspiciously motivated funding opportunities? Copyright concerns about training data? Where do you draw the line for your publication in regard to working with Big Tech companies whose choices are so-often demonstrably misaligned with the news industry? Using well-packed open-source software alternatives can help you avoid many of these relational risks. Or maybe using open-weight versions, where you can tune the model’s parameters to control behavior more directly, is a good middle ground for you?

Finally, consider the fact that generative AI tools are designed to statistically make things up. The large language models underlying chat-based interfaces are just giant systems trained on text to count how often words appear next to other words; they’re probabilistic Xerox machines. It is very hard to both validate their outputs and ensure reproducible results. Non-generative machine learning tools don’t introduce the same data quality risks, and many of them have already been validated through prior use and research evaluation processes.

Final Thoughts

A content audit may sound like a challenging high-tech undertaking, but The Scope’s case shows it’s within reach for small, mission-driven newsrooms if you can find a little technology assistance. With just a few free and affordable tools and some clear goals, you can gain valuable insights into your newsroom coverage’s strengths and areas for improvement. I encourage you to try these evolving approaches out, making critical and intentional decisions that engage with the ethical quandaries I’ve shared, as appropriate for your organization. Running any sort of content audit is going to help you assess, and demonstrate to your readers, how your content is in alignment with your mission and goals.

Originally published to the Generative AI in the Newsroom blog on Medium.